To

emphasise how boring life would be without images from our built

environment, this blog posting contains no pictures of buildings.

To

emphasise how boring life would be without images from our built

environment, this blog posting contains no pictures of buildings.

To

emphasise how boring life would be without images from our built

environment, this blog posting contains no pictures of buildings.

To

emphasise how boring life would be without images from our built

environment, this blog posting contains no pictures of buildings.

Until recently few

people would have understood the expression Freedom of Panorama.

Something to do with the iconic BBC TV current affairs programme

maybe? But this has all changed due to the ongoing debate (for

instance here,

here and here) within the EU about copyright reform. At the moment the opponents of Freedom of Panorama are in the ascendant. Freedom of Panorama is of

course about whether a photographer, videographer or artist may

freely record and then exploit images of sculptures or buildings

which are visible in public places, without seeking permission. In one

sense this issue highlights the wider problem of harmonising copyright law

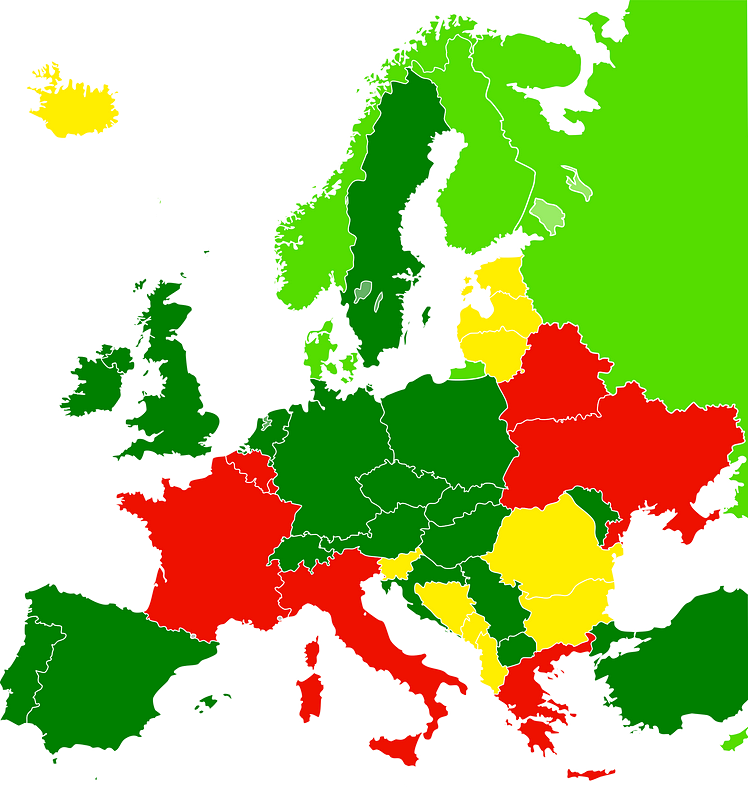

across the EU. One look at the map below shows graphically where the

'fault' lines lie.

|

| Map by King of Hearts and others, licensed CC BY-SA. |

(obviously not all the

countries shown are members of the EU)

Countries shown in red

forbid any such representations without permission, whereas those shown

in dark green fully embrace the Freedom of Panorama policy. The lighter green countries

only extend the exemption to buildings, not sculptures or similar

works. Those in yellow permit only the recording of such works in

public places for non-commercial use. It is perhaps too simplistic to

say that these divisions are roughly aligned to the division between

a more utilitarian view of copyright as a property right, and the droit d'auteur where the spirit of the author is exalted, but that

certainly goes some way to explaining the fundamentally opposing

positions taken over Freedom of Panorama.

The debate also highlights the

two different senses of 'public domain'. In the wider context many people think of the

public domain as that to which the public has access, such as the

internet, as well as physical public spaces. On the other hand copyright

enthusiasts use the words in a much more specific sense, namely the definition of the state of a work which is no longer subject to legal

copyright protection. A building thus represents the paradox of standing in the public domain but not being in the public domain.

This raises the question: why should a building be subject to copyright in the first place? Without doubt architects are usually skilled artists and designers, and it is clearly fair and reasonable that their drawings should be protected in the same way as other artistic works. But why shouldn't the element of expression of their ideas (and thus copyright) be limited just to the drawings alone? It is undoubtedly true that many buildings are beautiful objects in their own right, but so are some cars or clothes or culinary dishes, but we don't feel the need to protect these things through copyright.

Unlike other forms of the traditional copyright works (literary, dramatic, musical and artistic), and despite a passing mention in Article 5(3)(h) covering exceptions to the reproduction right, a building cannot be subject to the majority of the specific provisions of the InfoSoc Directive (2001/29/EC) such as the communication right, the making available right or the distribution right. So that immediately makes a building a special case, outside the general direction of travel of copyright reform which is largely concerned with ensuring that copyright law reflects current and emerging technological changes. Furthermore because a building per se cannot be published, distributed or translated, it is effectively a continuous public performance or broadcast of the architect's creativity, open to everyone at all times. There is no need for a decision about whether a new public is being communicated to, as per Svensson. And even if the argument for according copyright to a building is persuasive, should this really extend to preventing the making of visual copies of it? After all, such images in no way affect the economic or moral rights of the architect any more than the building itself does. A photograph of a building does not compete with either the building itself or with the architect's drawings, because it does not do serve the same purpose. Such images will, in the main, only serve to enhance the reputation and renown of the architect. Perhaps if copyright in a building was similar to design right, in that what was restricted was the creation of an actual real three dimensional full-scale copy of the building, that would make sense, since the architect might be expected to earn an additional fee for any second edifice. One also has to consider how buildings come about. Architects are usually commissioned to do the job; unlike artists or sculptors, their creativity is only allowed to see the light of day because of the patronage of developers. To use the American terminology, their work is for hire. The end product of their job is not a work of artistic craftsmanship, as it is not made by their own skilled hands, and the underlying purpose of a building is utilitarian. But perhaps most significantly, the design of a modern iconic building, such as the Shard in London or the Burj Al Arab in Dubai, is not the work of one person, but huge teams of engineers, architects and other specialists. While the outline concept may originate from the mind of a single individual, the execution is way beyond the capability of any one person. This strengthens my view that allowing copyright in a finished building is absurd because it stretches the idea of 'author' beyond rationality.

And there is the entirely separate, practical argument that as far as non-commercial photography etc is concerned, copyright in the physical building is virtually unenforceable due to today's ubiquity of cameras and smart phones. While the average person might think twice about downloading a pirated piece of music, it is unrealistic to believe they will ever see the moral case for not taking a selfie with the London Olympic Stadium or the Louvre in the background, without first seeking permission from the architect.

This raises the question: why should a building be subject to copyright in the first place? Without doubt architects are usually skilled artists and designers, and it is clearly fair and reasonable that their drawings should be protected in the same way as other artistic works. But why shouldn't the element of expression of their ideas (and thus copyright) be limited just to the drawings alone? It is undoubtedly true that many buildings are beautiful objects in their own right, but so are some cars or clothes or culinary dishes, but we don't feel the need to protect these things through copyright.

Unlike other forms of the traditional copyright works (literary, dramatic, musical and artistic), and despite a passing mention in Article 5(3)(h) covering exceptions to the reproduction right, a building cannot be subject to the majority of the specific provisions of the InfoSoc Directive (2001/29/EC) such as the communication right, the making available right or the distribution right. So that immediately makes a building a special case, outside the general direction of travel of copyright reform which is largely concerned with ensuring that copyright law reflects current and emerging technological changes. Furthermore because a building per se cannot be published, distributed or translated, it is effectively a continuous public performance or broadcast of the architect's creativity, open to everyone at all times. There is no need for a decision about whether a new public is being communicated to, as per Svensson. And even if the argument for according copyright to a building is persuasive, should this really extend to preventing the making of visual copies of it? After all, such images in no way affect the economic or moral rights of the architect any more than the building itself does. A photograph of a building does not compete with either the building itself or with the architect's drawings, because it does not do serve the same purpose. Such images will, in the main, only serve to enhance the reputation and renown of the architect. Perhaps if copyright in a building was similar to design right, in that what was restricted was the creation of an actual real three dimensional full-scale copy of the building, that would make sense, since the architect might be expected to earn an additional fee for any second edifice. One also has to consider how buildings come about. Architects are usually commissioned to do the job; unlike artists or sculptors, their creativity is only allowed to see the light of day because of the patronage of developers. To use the American terminology, their work is for hire. The end product of their job is not a work of artistic craftsmanship, as it is not made by their own skilled hands, and the underlying purpose of a building is utilitarian. But perhaps most significantly, the design of a modern iconic building, such as the Shard in London or the Burj Al Arab in Dubai, is not the work of one person, but huge teams of engineers, architects and other specialists. While the outline concept may originate from the mind of a single individual, the execution is way beyond the capability of any one person. This strengthens my view that allowing copyright in a finished building is absurd because it stretches the idea of 'author' beyond rationality.

And there is the entirely separate, practical argument that as far as non-commercial photography etc is concerned, copyright in the physical building is virtually unenforceable due to today's ubiquity of cameras and smart phones. While the average person might think twice about downloading a pirated piece of music, it is unrealistic to believe they will ever see the moral case for not taking a selfie with the London Olympic Stadium or the Louvre in the background, without first seeking permission from the architect.

Many prominent architects are

also particularly proficient at self-publicity and so one has to

wonder exactly who is lobbying the European Parliament and Commission

to ensure that Freedom of Panorama is excluded from any future EU law. Although if in

doubt we can usually blame the French. Or possibly French architects.

As Ben has previously reported, the next milestone along the road to EU copyright reform comes on 9 July when the plenary session of the European Parliament debates the subject. Perhaps at that point the 'greens' (as shown on the map above) may manage to sway the argument back the other way.

For Eleonora's take on the subject, see this IPKat posting.

For Eleonora's take on the subject, see this IPKat posting.

Andy I am in complete agreement with you. A photo of a building or a sculpture is not a building or a sculpture (let alone a copy of a building or a sculpture.) And how a photo of a complex bit of built environment, made up of many structures ,assembled over longish years ,could be a breach of ,anybody in particulars , economic rights is beyond me.

ReplyDeleteAs for motive ,suggest if panoramic photos were made a breach ,that there would then be room to argue for some sort of levy , administered by some sort of collection society, to compensate right holders for private photography-copying of streetscapes,buildings, and sculptures,no?